When he moved to San Francisco in 1892, Homer Davenport worked first—after a brief stint at the Mark Hopkins Art School—for Hearst’s Examiner. He was let go, apparently due to his “lack of artistic skill.” He then found work, at a higher salary, on Michael de Young’s San Francisco Chronicle, before eventually being re-hired by the Examiner, (at Hearst’s personal request) for an even higher salary in 1894.

This period has been lacking, not only in content, but in relevant facts relating to this period, which included a brief stint in Chicago drawing horses for the Herald during the 1893 World’s Fair, before returning to the Bay Area and de Young’s Chronicle.

I discovered “Fold3,” an outstanding online historical archive, that had relatively high resolution scans of each and every page of that San Francisco publication. I discovered a number of examples of Davenport’s work, hereto unseen for over a century. Many include dramatic outdoor scenes of horses and hunting.

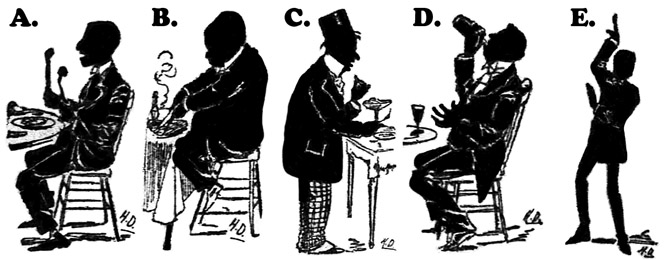

One series stood out, and represents some of his earliest published work. It contains five illustrations by Davenport that were published in the February 19, 1893 edition. A seasonal column, it was titled “In Sack-cloth and Ashes,” and featured a tongue-in-cheek overview of how various noted citizens observed (or not) the Christian fast of Lent.

These pieces employed a “silhouette” technique. He also used this effect in the only surviving comic strip he did—featuring himself as the foil, with pigeons in Venice’s St. Marks Square. The quality of course is what would be expected from online reproductions by way of archival microfilm, but still shows the gist of his illustrated jests. With one exception, his Chronicle work was signed with his initials, “H.D.” like some of his previous work on the Portland Oregonian. It could be assumed that newspaper artists had to earn the right to even have their initials included, so there may well be more images he drew that remained un-signed. Most of the “cuts” are anonymous, and were similar in form and function to our current concept of “clip-art.”

The author of the column is unknown, perhaps by design, as the tone and tenor of the article could conceivably be interpreted as border-line blasphemous by some. This would not have deterred Davenport however, having been raised by “intellectual infidels” in Silverton, Oregon. Below are the original captions, with relevant passages from the original column.

A: Louis Lissak runs to eating because it disagrees with him. “That’s just it; I am careful of my stomach for ten months and a half during the year, and when Lent comes I let loose and eat everything my depraved and gluttonous appetite calls for. I get sick then. That is my penance.”

A: Louis Lissak runs to eating because it disagrees with him. “That’s just it; I am careful of my stomach for ten months and a half during the year, and when Lent comes I let loose and eat everything my depraved and gluttonous appetite calls for. I get sick then. That is my penance.”

B: Bob Grayson makes penance by eating a tough steak. “Bob Woodward is a better man than I at almost any stage of life,” he acknowledged in his own modest way, “and he quit the table right after the fish was eaten. But I think I did more penance than he will in the balance of this season by trying to chew through the steak they served me. The weight of that leather boot top, with a fine French sauce, I swallowed is resting now with a deadly weight right under my chamois chest protector.”

C: Eddie Dunn comes 3000 miles from New York to eat rubber doughnuts. Dunn has been a little wild in his day, and decided he would leave the tempting haunts of New York, travel 3000 miles and repent during lent by feeding upon one of the lunch counters of a first-class saloon in this city. The tank was more than he could stand when he discovered that the cold pig’s feet and brown rounded doughnuts were some of the most perfect products of the rubber company.

D: Johnny Byrnes ends his mortification in wine. “I refrain from intoxicants the whole year round,” he says, “because they do not agree with me. When I cover myself with sackcloth and ashes I start in the day before and drink beer, topping it off at night with wine, and the next morning I feel that I am buried in the debris.”

E: J. B. Casserly neither borrows nor lends during lent. “I am mortifying my friends,” he said, “more than I mortify myself. During the penitential season I neither borrow nor lend—especially the latter.”

After marching all afternoon and having our photos taken, the big parade started at eight o’clock. After marching in the parade until nearly midnight it came our turn to stop and play before the reviewing stand. Most of us were so sleepy we could hardly keep our eyes open, and the horn blowers were a sorry lot. Between their new shoes and their lips, they were about done up. Their upper lips hung out far and were purple. They looked like they had all got into a bee’s nest and had been stung on the lips. The leader cautioned each member that the supreme moment of our lives was upon us; that all the other bands were present, and that he thought Cleveland himself was.

After marching all afternoon and having our photos taken, the big parade started at eight o’clock. After marching in the parade until nearly midnight it came our turn to stop and play before the reviewing stand. Most of us were so sleepy we could hardly keep our eyes open, and the horn blowers were a sorry lot. Between their new shoes and their lips, they were about done up. Their upper lips hung out far and were purple. They looked like they had all got into a bee’s nest and had been stung on the lips. The leader cautioned each member that the supreme moment of our lives was upon us; that all the other bands were present, and that he thought Cleveland himself was.