Introduction: Through Ebay, I recently obtained a selection of nine original pages from the October, 1902 number of The Strand Magazine from London. This was an article entitled The American Cartoonist and His Work by Arthur Lord and featured short bios and examples of four “famous” cartoonists of the day: Homer Calvin Davenport, William Allen Rogers, John Tinney McCutcheon and Rowland Claude Bowman. What I found interesting in this piece, besides the fact that it opened with Davenport, was the noted variations between styles of the four chosen by this British author, to represent the “American Cartoon” community.

Introduction: Through Ebay, I recently obtained a selection of nine original pages from the October, 1902 number of The Strand Magazine from London. This was an article entitled The American Cartoonist and His Work by Arthur Lord and featured short bios and examples of four “famous” cartoonists of the day: Homer Calvin Davenport, William Allen Rogers, John Tinney McCutcheon and Rowland Claude Bowman. What I found interesting in this piece, besides the fact that it opened with Davenport, was the noted variations between styles of the four chosen by this British author, to represent the “American Cartoon” community.

The deeper I dig into the history of Davenport and his world, the more surprises I find. W.A. Rogers I had been familiar with for years, as his career extended into fine art as well as cartooning. J.T. McCutcheon I chanced upon earlier this year in a small county history museum in Richmond, Indiana. And subsequent research reviled that he and Davenport were acquaintances of one another, as detailed elsewhere within these pages. He, like Rogers had a long and distinguished career, with numerous collections of his work readily available.

The forth cartoonist profiled in this article was a pleasant surprise. I had never heard of R.C Bowman, but was immediately taken by his interesting style. There was very little information on him, with the bulk of it gleaned from the blog of a contemporary cartoonist, Mr. Paul Berge. He had one of Bowman’s books, a collection of cartoons he did for the Minneapolis Tribune, and posted them on his blog. He also did his own research and uncovered a few additional facts:

“I turned to the listserve of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. J.P. Trostle referred me to the Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. There I discovered that Bowman’s full name was Rowland Claude Bowman, and that he lived from 1870 to 1903. It also appears that the OSU BICL&M might have a copy of the 1903 book, and I hope it’s in better condition than my copy of the 1901 edition.”

His relative obscurity today, not unlike Davenport’s, is no doubt due to his early demise, at the age of 33. Obviously, room for much more research! At any rate, here is the entire article, reproduced here with the original illustrations. The high-quality printing process employed by The Strand Magazine can be seen in these reproductions. This also allowed for a relatively easy “OCR” process to convert the text as well. Note, that as a product of the UK, the grammar and spellings represent standard usage of “The King’s English,” from the other side of the big pond. These I have left as-is. Enjoy!

The Strand Magazine, October 1902

The American Cartoonist and His Work

by Arthur Lord

He who first wrote of the political cartoon as a “picture editorial” writ better than he knew. He invented a term which expresses the thing exactly. Since the days of Hogarth and Gillray there have been “cartoons,” “caricatures,” “political sketches,” or “pencillings,” as Punch once called them, but no one has been able to classify all varieties of work and style under one distinctive head. Here, however, we have a double-barreled title which shoots unerring to the mark.

It is a term pretty in its connotation. It carries us back to the time when the influence of the editorial first began to wane and something equally potent began to take its place. That “something” was the political or social cartoon, daily or weekly enforcing a lesson which might well have been enforced in type had not the public got tired of written sermons. Editors were not slow to recognize that the printed picture contained more power for good than a column of double-leaded lines. The man in the street, it was noted, would stop to look at the picture before he tossed his paper into the mud, and the audience to which the picture appealed became almost as numerous as the people in the street. The cartoon took unto itself a cumulative increase in power, and the improved mechanical appliances in newspaper illustration made it well-nigh impossible for any modern newspaper, pressed as its editorial columns are by the competition in, and acquisition of, news, to succeed in bringing home moral lessons to the public without the aid of the editorial drawn by an artist’s hand. The change from old conditions to new occurred with greatest rapidity in the United States, where the editors are as prompt in observing what the public wants as the public is quick in showing what it likes, and it is with these “picture editorials” and their American makers that this series of articles has to deal.

There are many who look upon Mr. Homer Davenport (left), as the leading cartoonist in the United States. This noted draughtsman possesses many of the qualities which should entitle him to the most prominent consideration; yet it is well that the real question of his pre-eminence should be left open to doubt. He works, it is true, for one of the most widely circulated papers in America. His fertile brain and facile pen have full swing. He attacks with uncommon straightforwardness, and at times a positive brutality, all the evils of the day, either social or political, and his cartoons go direct to the heart and intellect of the American people. His picture editorials speak with no uncertain voice, and if the results of one’s preaching were to entitle any cartoonist to the position of pre-eminence in the cartooning ranks, then Davenport would be first and all others behind.

But in work of this sort something more than mere effectiveness should be considered. There are numerous workers on the American pictorial Press who, if somewhat less skillful than Davenport in hitting the bull’s-eye of public appreciation, are in every way better draughtsmen. They wield their pencils with more technical accuracy, and each cartoon they draw is a lesson in the best newspaper art. Davenport makes no pretense to being a great artist. He has lacked the training which others happily possess, and his success is due rather to his brutal effectiveness in the objective treatment of a subject than to his technical manipulation of line.

He is a rapid worker, and has been known to discard half-a-dozen drawings before satisfying his own criticism. He has improved in his work conspicuously while he has been on New York Journal, and if he still finds it impossible correctly to draw the human form in a variety of action, he has come dangerously near making Presidents. As Gillam invented the “tattooed man” in the Blaine campaign of twenty years ago, so has Davenport given to Hanna a dollar-marked store suit which has become inseparably associated with the name of our great political organizer.

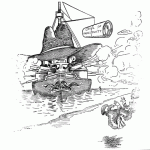

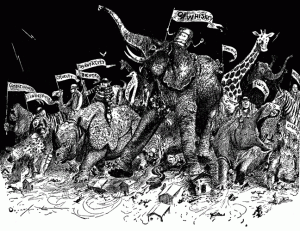

Recently his cartoons in the Journal have enforced moral lessons, such as the evils of whisky, gambling, church bigotry, etc., and one of these, called “Conquerors and Enslavers of Mankind—Whisky Leads the Horde,” we are able to reproduce. A more powerful cartoon, perhaps, was that called “Whisky—That’s All,” which represented a woman and three or four children standing by the coffin of husband and father in a poverty-stricken room. Here was a moral lesson enforced with a poignancy which, according to the opinion of many judges, should be totally outside the province of the newspaper cartoon. Davenport and the paper he works for evidently thought otherwise, and it is not for us to say that they were incorrect.

Davenport was born in a small Oregon town in 1867, and in his thirty-five years of life has been at different times a jockey, railroad fireman, and circus clown. He possesses no school education. In 1892 the San Francisco Examiner gave him employment, and in 1895 Mr. Hearst took him to New York, where he has since lived and worked. It was against him and his cartoons that the attempt was made in 1897 to pass the Anti-Cartoon Bill in New York. Besides the Hanna suit, which we have already mentioned, Davenport invented the well-known giant Trust figure in 1899, and from a Republican point of view it is not entirely to his credit that he nearly made Bryan President.

In an article recently published in a San Francisco weekly Mr. Davenport has told the interesting story of his own career. Much of this is an elaboration of the main facts just cited, but the artist has something to say about his methods which should here be re-told. “With me,” he writes, “as with all cartoonists, I suppose, there, is that feeling within the soul that there is a great cartoon of national and international importance that will someday be drawn. I am striving to that end, and I hope someday to achieve my ambition.”

“I love,” he continues, “to draw strong cartoons, in the line of brute force, but I prefer those of the pathetic order, and I am satisfied that between the two lies the real power of cartooning. Humorous cartoons are pleasing and restful, but they don’t leave the lasting impression that should go with serious work. My work has been a great pleasure to me, and the greatest reward it ever brought me was when Admiral Dewey, sobbing like a child, told me that my cartoon, ‘Lest We Forget,‘ drawn in his behalf when the of the nation were a people abusing him, prompted him to content himself in America when he was seriously thinking of going abroad to make his home.”

The name of Mr. W. A. Rogers (right), is possibly best known to our readers through the cartoons which for many years have appeared in Harper’s Weekly. There are those who hold that Rogers is greater even than Thomas Nast, who worked for the same periodical. Nast could not draw a human foot correctly; Rogers can. He is a thorough artist as well as an effective moral preacher, and some of his attacks upon bad government in New York City have passed into municipal history.

The name of Mr. W. A. Rogers (right), is possibly best known to our readers through the cartoons which for many years have appeared in Harper’s Weekly. There are those who hold that Rogers is greater even than Thomas Nast, who worked for the same periodical. Nast could not draw a human foot correctly; Rogers can. He is a thorough artist as well as an effective moral preacher, and some of his attacks upon bad government in New York City have passed into municipal history.

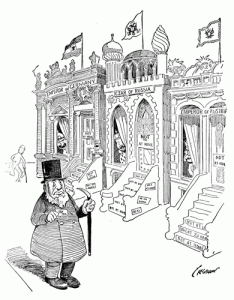

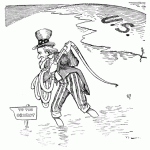

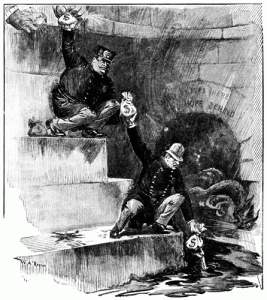

The cartoon which we reproduce, called “How High Up Does It Go?” (left), probably made the strongest impression of anything Rogers ever did, and it was so distinctly serious in tone that it appealed particularly to the intellectually-minded, who hold that cartoonery should be something else than buffoonery. When published in Harper’s Weekly this cartoon was commented upon widely by the public Press, and a large number of letters flowed in upon the publishers from many parts of the United States complimenting both paper and artist upon the masterly and compelling qualities of this memorable attack upon municipal corruption.

For those who, in their knowledge of the evils of to-day, have forgotten the evils of yesterday, it may be well to say that Rogers in this cartoon pictures a sewer flowing with filth, a series of stone steps leading upwards, with a policeman on the lower step, a captain of police on the step above, and higher up a pair of clutching jeweled hands. As the captain passes his bags of money to the hands above he deducts his part of the spoil, the policeman receiving the bags from a woman’s hand stretched out from the eddies of filth in the sewer. Municipal degradation could have gone no farther in the days when this cartoon was made, and we doubt if anyone beside Rogers could have so fitly exposed such degradation to the public view.

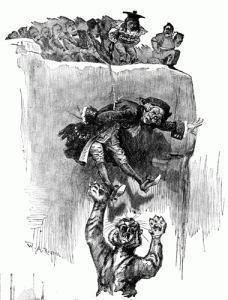

Another of Rogers’s cartoons, called “Father Knickerbocker’s Peril” (right), showed a good little “Goo-goo,” or good Government club, refusing to help poor Father Knickerbocker out of the clutches of the Tammany tiger because he did not approve of the others who were trying to rescue him. The little “Goo-goo” is now forgotten, but the moral of the cartoon remains. President Roosevelt told Rogers a short time ago that he considered it about the best thing the artist had ever done.

Another effective cartoon is that called “The Turk and the Christians” (left), intending to show-that the stake does not always go to the winner. It was published in Harper’s Weekly during the Greco-Turkish War, and excited considerable attention. Rogers was born in Springfield, Ohio, in 1854, and, after being educated in the common schools, was employed in business offices until his eighteenth year. He was on the staff of the New York Daily Graphic in 1872-3, and was engaged by Harper’s Weekly in 1877; for which paper he has worked almost continuously since.

The wide difference that exists between humorous and serious cartoon work is admirably shown by a comparison between the examples of Davenport and Rogers, which we have just passed, and the following examples from the pens of McCutcheon and Bowman. At first glance it might appear that the difference was a mere distinction between East and West, for McCutcheon and Bowman possess the Western spirit, whereas Davenport and Rogers speak with the more serious language of the East. The two Western men are genuinely funny, and their work shows the quality of caricature as it is more familiarly known. There is a burlesque broadness about it that appeals — and we hope it may be said without offense to the Western mind — to the less developed intellect of the new and enterprising homogeneous civilization.

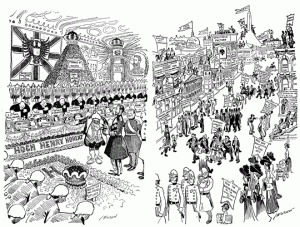

They look at things in a new way in this wonderful West of ours. They see the comic side of life. They are just a little vulgar, but it is a vulgarity which does not wholly annoy, and if there is a suspicion shoddiness in the social side of life, it is that same shoddiness which the cartoonist delights to bring before the public. John T. McCutcheon (left), in his remarkable series of cartoons published in the Chicago Record-Herald at the time of Prince Henry’s visit, called “The Cartoons that Made Prince Henry Famous,” went almost as far as it is possible to go in exposing the pretensions of the vulgar rich, their fervid hunt for recognition by those of Royal houses, and the tendency to toadyism which at such a time is, in certain classes, let loose. It is said that Prince Henry was so pleased and impressed by McCutcheon’s cartoons that, at the request of the Imperial German Consul, the originals were presented to him and were sent framed to Kiel.

They look at things in a new way in this wonderful West of ours. They see the comic side of life. They are just a little vulgar, but it is a vulgarity which does not wholly annoy, and if there is a suspicion shoddiness in the social side of life, it is that same shoddiness which the cartoonist delights to bring before the public. John T. McCutcheon (left), in his remarkable series of cartoons published in the Chicago Record-Herald at the time of Prince Henry’s visit, called “The Cartoons that Made Prince Henry Famous,” went almost as far as it is possible to go in exposing the pretensions of the vulgar rich, their fervid hunt for recognition by those of Royal houses, and the tendency to toadyism which at such a time is, in certain classes, let loose. It is said that Prince Henry was so pleased and impressed by McCutcheon’s cartoons that, at the request of the Imperial German Consul, the originals were presented to him and were sent framed to Kiel.

A mere glance at the selection we have made from this entertaining series shows the good and bad qualities of McCutcheon’s style. He possesses splendid ability in depicting action, and his manipulation of crowds is noteworthy. He possesses a rough and ready facility in facial expression, and can do much in the least possible number of lines. The captions in his cartoons are among his happy hits; and that he thought of the Prince Henry series and carried it to such a successful conclusion in the short time allowed him by the exigencies of newspaper illustration and the feverish haste of the German Prince’s tour is the best evidence of his ability as a topical illustrator. McCutcheon’s faults are due perhaps to this same pressure under which cartoonists abhour. There is an unfinished appearance about his work, an exaggeration of detail, and a slight tendency towards that vulgarity in subject treatment which we have mentioned as common to Western draughtsmanship. Were his cartoons, however, less full of faults they would not be half so funny.

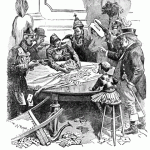

An early cartoon — “At Last Mr. Harrison Has Come Out of the Wood” (left) — is in many ways the best thing McCutcheon ever did, and we are glad to know that the artist himself looks upon it as his best. The episode which brought it into being is now almost forgotten, except by those who follow political movements closely, but the political movement of the late Mr. Harrison shown in this cartoon is interesting from the first footstep to the last. We speak under correction, but we are prompted to believe that the figure of cowboy Teddy, with his pistol and sombrero, is the first appearance of that famous figure in political illustration. Another of McCutcheon’s cartoons, “Oom Paul Calls on Some Gentlemen of Europe” (below right) is one of those on the subject of the South African War which attracted attention and was widely reprinted in the early days of that struggle.

An early cartoon — “At Last Mr. Harrison Has Come Out of the Wood” (left) — is in many ways the best thing McCutcheon ever did, and we are glad to know that the artist himself looks upon it as his best. The episode which brought it into being is now almost forgotten, except by those who follow political movements closely, but the political movement of the late Mr. Harrison shown in this cartoon is interesting from the first footstep to the last. We speak under correction, but we are prompted to believe that the figure of cowboy Teddy, with his pistol and sombrero, is the first appearance of that famous figure in political illustration. Another of McCutcheon’s cartoons, “Oom Paul Calls on Some Gentlemen of Europe” (below right) is one of those on the subject of the South African War which attracted attention and was widely reprinted in the early days of that struggle.

The Record-Herald is to be congratulated on having in McCutcheon one whose pen is ever ready either for writing or illustration. We may call him a cartoonist, but he is a correspondent as well. He has been connected with the Record-Herald since 1889, when he was nineteen years of age, and became prominent through his cartoon work in the campaign of 1896. In his cartoons of this time he introduced a queer and wonderful little dog which trotted beside caricatures of Bryan and Hanna, and formed a conspicuous part in various drawings of parades and other political satires. In 1897, through an invitation from the Treasury Department, McCutcheon started on a tour round the world on the revenue cutter McCulloch, and reached Hong Kong in time to join Admiral Dewey before the American fleet went to Manila. He was on board that vessel during the Battle of Manila Bay, served until April, 1900, as a correspondent in the Philippines and the Far East, then went to the Transvaal to represent his paper on the Boer side, and returned to America in 1900, again to take up cartoon work. Since that time he has been constantly engaged in illustration, and to-day possesses one of the best-known names as a highly-paid, up-to-date, and forceful caricaturist. McCutcheon is essentially good-natured in all that he does.

The Record-Herald is to be congratulated on having in McCutcheon one whose pen is ever ready either for writing or illustration. We may call him a cartoonist, but he is a correspondent as well. He has been connected with the Record-Herald since 1889, when he was nineteen years of age, and became prominent through his cartoon work in the campaign of 1896. In his cartoons of this time he introduced a queer and wonderful little dog which trotted beside caricatures of Bryan and Hanna, and formed a conspicuous part in various drawings of parades and other political satires. In 1897, through an invitation from the Treasury Department, McCutcheon started on a tour round the world on the revenue cutter McCulloch, and reached Hong Kong in time to join Admiral Dewey before the American fleet went to Manila. He was on board that vessel during the Battle of Manila Bay, served until April, 1900, as a correspondent in the Philippines and the Far East, then went to the Transvaal to represent his paper on the Boer side, and returned to America in 1900, again to take up cartoon work. Since that time he has been constantly engaged in illustration, and to-day possesses one of the best-known names as a highly-paid, up-to-date, and forceful caricaturist. McCutcheon is essentially good-natured in all that he does.

Mr. R. C. Bowman, of the Minneapolis Tribune, belongs also to the ever-spreading good-natured school. This artist, who began at the age of nineteen on the Arkansas Traveler, has devoted about twelve years to caricature, and he possesses theories about his work which many a less-known man might take to heart, with accruing advantage to himself and the public. Bowman believes — and the strength of his belief is shown in the specimens of his work here reproduced — that a cartoon can be to the point without malicious, and that it is not necessary to make ogres of men in order to show that you differ with them politically. A running glance at his various cartoons shows that Bowman has pronounced ideas of right and wrong, and that he takes his stand conscientiously on all matters of social and political import, but you will hunt in vain for any trace of partisan spleen.

Mr. R. C. Bowman, of the Minneapolis Tribune, belongs also to the ever-spreading good-natured school. This artist, who began at the age of nineteen on the Arkansas Traveler, has devoted about twelve years to caricature, and he possesses theories about his work which many a less-known man might take to heart, with accruing advantage to himself and the public. Bowman believes — and the strength of his belief is shown in the specimens of his work here reproduced — that a cartoon can be to the point without malicious, and that it is not necessary to make ogres of men in order to show that you differ with them politically. A running glance at his various cartoons shows that Bowman has pronounced ideas of right and wrong, and that he takes his stand conscientiously on all matters of social and political import, but you will hunt in vain for any trace of partisan spleen.

During the five years he has been with the Tribune his output has been as enormous as its scope has been varied, and he friendships he has made have been not only among those of his own party, but also among his political foes. The man who laughs most heartily at a cartoon when that cartoon is good – humoured is very often the subject of the cartoon himself. Where Davenport, in short, would make an enemy, Bowman would make a friend, so great is the difference in the styles of the two men. Bowman is a careful student of politics, and his picture editorials always present a strong argument. He possesses a rare originality and spontaneous humour, and that his drawings are well thought out is proved by their simplicity in detail. It is not too much to say that in connection with the work of Bartholomew, of the Minneapolis Journal, which will be treated of in our next article, the topics of the times are more effectively illustrated by these two cartoonists than by any others in the United States. Bowman is a humorist and not a satirist, and has attained his success through close adherence to well-defined principles of directness, simplicity, and gentleness. The Tribune reader opens his paper with the knowledge that he is going to get a laugh, and the man made fun of may open his copy with the knowledge that he is not going to squirm.

During the five years he has been with the Tribune his output has been as enormous as its scope has been varied, and he friendships he has made have been not only among those of his own party, but also among his political foes. The man who laughs most heartily at a cartoon when that cartoon is good – humoured is very often the subject of the cartoon himself. Where Davenport, in short, would make an enemy, Bowman would make a friend, so great is the difference in the styles of the two men. Bowman is a careful student of politics, and his picture editorials always present a strong argument. He possesses a rare originality and spontaneous humour, and that his drawings are well thought out is proved by their simplicity in detail. It is not too much to say that in connection with the work of Bartholomew, of the Minneapolis Journal, which will be treated of in our next article, the topics of the times are more effectively illustrated by these two cartoonists than by any others in the United States. Bowman is a humorist and not a satirist, and has attained his success through close adherence to well-defined principles of directness, simplicity, and gentleness. The Tribune reader opens his paper with the knowledge that he is going to get a laugh, and the man made fun of may open his copy with the knowledge that he is not going to squirm.

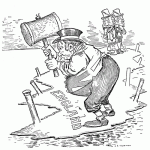

Look, by the way, at Bowman’s cartoons, and see if you can find the dog. The Bowman dog has become famous. This remarkable little canine, which the cartoonist introduces into nearly all his work, is full of expression, and the keynote to the story is often to be found in the antics of the pup. If he is scared, in common with the elephant and the donkey (above right), at the advent of the Third Party, you will find him running into the distance with marvelous alacrity. He rests, with wonder-eyed demureness, beside Carnegie and Morgan while John Bull tacks down his island (left), and when the battleship Kentucky arrives off the coast of Turkey (below right) he is—well, find him for yourself. If the small boys of Minneapolis, as it is said, may be seen chalking Bowman’s dog on side-walks and fences, it is a proof of the popularity of the cartoonist which needs no further to be proved.

Look, by the way, at Bowman’s cartoons, and see if you can find the dog. The Bowman dog has become famous. This remarkable little canine, which the cartoonist introduces into nearly all his work, is full of expression, and the keynote to the story is often to be found in the antics of the pup. If he is scared, in common with the elephant and the donkey (above right), at the advent of the Third Party, you will find him running into the distance with marvelous alacrity. He rests, with wonder-eyed demureness, beside Carnegie and Morgan while John Bull tacks down his island (left), and when the battleship Kentucky arrives off the coast of Turkey (below right) he is—well, find him for yourself. If the small boys of Minneapolis, as it is said, may be seen chalking Bowman’s dog on side-walks and fences, it is a proof of the popularity of the cartoonist which needs no further to be proved.

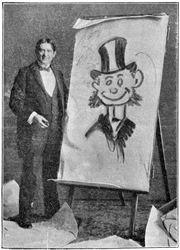

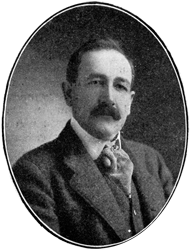

Bowman has a great fondness for children, and we believe it is his highest ambition to become a successful writer of child verse. He has already published one volume which contains verses of this sort, that may reasonably be compared with the late Eugene Field’s. He is also a “chalk talker,” and indulges now and then in a funny lecture which he illustrates with his own hand. In our photograph we may see him, an able-bodied, happy, and good-natured gentleman, standing by the side of his blackboard as if in lecture pose, and from the appearance of the man and the examples of his work reproduced in this article we may easily understand the quality of the reputation made by him throughout the great and enterprising West.

Bowman has a great fondness for children, and we believe it is his highest ambition to become a successful writer of child verse. He has already published one volume which contains verses of this sort, that may reasonably be compared with the late Eugene Field’s. He is also a “chalk talker,” and indulges now and then in a funny lecture which he illustrates with his own hand. In our photograph we may see him, an able-bodied, happy, and good-natured gentleman, standing by the side of his blackboard as if in lecture pose, and from the appearance of the man and the examples of his work reproduced in this article we may easily understand the quality of the reputation made by him throughout the great and enterprising West.

Incidentally, in our treatment of the men, we have dropped a hint or two as to the qualifications necessary for successful cartoon work. In so far as nearly every paper of importance in the United States goes in for this form of illustration, and as nearly all the principal journals are partisan, it is obvious that the competition between newspapers for the services of the best draughtsmen is intense, and the successful cartoonist is the man who most effectively expresses the political tenets of his paper. On newspapers independent in politics the cartoonist’s office is no sinecure, and often the artist has to sacrifice his own independence of thought in order to make his work correspond with the “ideals” of the managing editor. Where, however, the cartoonist’s honest feelings coincide with the party feelings of the paper he represents we get the sappiest of results, for no man preaches so effectively as when he preaches what he really believes. We know of cases where Republican cartoonists have done extremely clever work for Democratic journals, just as we may find cases where editorial writers with Democratic leanings have been engaged at high salaries to write Republican editorials, but success in such cases is the exception rather than the rule.

Incidentally, in our treatment of the men, we have dropped a hint or two as to the qualifications necessary for successful cartoon work. In so far as nearly every paper of importance in the United States goes in for this form of illustration, and as nearly all the principal journals are partisan, it is obvious that the competition between newspapers for the services of the best draughtsmen is intense, and the successful cartoonist is the man who most effectively expresses the political tenets of his paper. On newspapers independent in politics the cartoonist’s office is no sinecure, and often the artist has to sacrifice his own independence of thought in order to make his work correspond with the “ideals” of the managing editor. Where, however, the cartoonist’s honest feelings coincide with the party feelings of the paper he represents we get the sappiest of results, for no man preaches so effectively as when he preaches what he really believes. We know of cases where Republican cartoonists have done extremely clever work for Democratic journals, just as we may find cases where editorial writers with Democratic leanings have been engaged at high salaries to write Republican editorials, but success in such cases is the exception rather than the rule.

Pingback: Hospital Bed Endowment | The Davenport Project